Analysis of Flannery’s ‘Now or Never’ Using Future’s Tools

April 26, 2011 Leave a comment

This was a lot of fun to write and quite challenging. It’s an analysis of Tim Flannery’s 2008 thesis ‘Now or Never’ which you can find here. I find the futures field extremely interesting, challenging and confronting however due to the idea of no one knowing or owning the future(s) sometimes practitioners can get a little lost in their own seriousness. The challenge with this seriousness is it can create a polarity which I believe defeats the purpose of the field, creating antagonism rather than openness and diversity of thought. I do admit that my opinion could be influenced by a small sample of experience where I experimented with the work I delivered finding when I wrote what I knew the audience wanted to hear I was well received, however when I challenged conventional thought (ironically what Flannery is trying to do) I was rejected. Anyway enjoy the read and do read Flannery’s thesis first as it will better inform you on a debate to which we all have an important role.

Introduction

Flannery’s (2008) thesis is divided into eight sections providing a useful framework for analysis. The sections are outlined in ‘Now or Never’ synopsis (table 1) illustrating thematic discourse. Subjects of detail will be analysed however a holistic (Nisbett et al. 2001) approach will be attempted in order that differences of opinion on minutiae will be neutralised. This will provide a basis through which judgement will be made as to the practicality of Flannery’s (2008) concepts, ideas, beliefs and futures.

‘Now or Never’ Synopsis

In the year 4 billion

Outlines issues faced by humanity through exceeding Earths bio-capacity and humanity’s place in the Gaian (Lovelock 2006) system. Two questions underpin his thesis; “What is our purpose as a species? And how does the earth work” (Flannery 2008, p 3)? Through Judeo-Christian ethic, Flannery (2008) posits humanity is poised, through a deep understanding of Earth’s regulatory system, to become Earth’s consciousness/brain.

The climate problem

Global population and the curbing of growth are acknowledged as long-term goals however the immediate crisis of climate change is identified. To address this issue, Flannery (2008) divides the Earth into its systematic parts (Meadows 2008) of crust, air and water. In this way he explains the cycle of carbon and its (and humanity’s additional) impact on the planet.

A new dark age?

In using Lovelock’s (2006) theory of Gaia, Flannery (2008) now takes a diametrically opposed stance to the thesis of humanity’s lack of foresight and ability to change. Even though the climate data has proven to be underestimated and black swans (Taleb 2008) not anticipated, Flannery (2008) believes that humanity still has a few years before the tipping point of no return. He has faith in humanity’s ability to invent new technology to save itself from Lovelock’s (2006) dire future.

The coal conundrum

Flannery (2008) delves deeper into humanity’s reliance on carbon energy sources by analysing the science, finding that data and scenarios are grossly underestimated. He posits that the industry and government needs to take a leadership stance but the vision for change is lacking. Clean coal technological solutions such as CO2 geological storage are suggested; acknowledging coal energy sources are a global reality that cannot easily be removed.

Geothermia

Flannery (2008) now moves into solution context. His belief is that Australia is well positioned to lead the required change by developing clean coal and geothermal power. He develops a future where carbon neutral cities emerge around geothermal energy sources and justifies his assertion through technological developments in Iceland, UAE and Denmark. In these situations vision and leadership provides economic and social benefit.

Trees for security

In this approach Flannery (2008) returns to the issue of preserving and developing carbon sinks. He acknowledges that forests play a role in stabilising climate and that a majority of the world’s poor partake in unsustainable practices. The proposed solution is an auction based economic system creating financial trading to persuade unsustainable practices to be changed. This system allows for underprivileged societies to enter the first rung of global prosperity.

Revolution in the feedlot

The issue of production and consumption is tackled and its impact on carbon production. Flannery (2008) offers practical solutions in pyrolysis and holistic farming practices whilst discussing their adoption barriers. The notion of sustainable diets and a labelling system is introduced to advertise carbon miles as a way of allowing the consumer to decide value.

The age of sustainability

Flannery (2008) introduces the last section with a pessimistic assessment that humanity could pass the point of no-return and now the issue is impact minimisation rather than avoidance. The question has turned to situations of causality through understanding impacts of teleological decision-making. This is a reality where social Darwinism has no place due to the acknowledgement that win/lose scenarios result in loss for all. To conclude Flannery (2008, p 63-64) chooses to remind the reader that evolutionary social change has previously occurred and that society has an opportunity, which ungarnered will mean that “all of our species’ great triumphs, all of our efforts, will have been for naught.”

Balance of argument

On the surface, the weight of Flannery’s (2008) argument is posed in a dialectical methodology as problem and solution, theory and practicality. The beginning of the text is heavily problem oriented to hook the reader into understanding the gravity of the situation and the individual’s role within the holistic system (Meadows 2008 ; Nisbett et al. 2001). Throughout the progression of Flannery’s argument the dialectical balance sways to practicality and solutions. However this superficial analysis doesn’t consider the ontological, phenomenological and teleological messages that reside in the text. To understand these constructs, more rigorous analysis is required and is presented in the following sections.

Table 1: Now or Never Themes

| In the year 4 billion | The climate problem | A new dark age? | The coal conundrum | Geothermia | Trees for security | Revolution in the feedlot | The age of sustainability |

| Exceeded Earth’s biocapacity | Limit population growth to 9 billion | Lovelock’s (2006) vision of an apocalyptic future resulting from a lack of foresight, wisdom and political energy | Carbon emissions need to be drastically reduced | Brings the challenge down to a domestic level in attempt to discuss Australia’s leadership potential | Turns to flora as carbon sinks particularly the forest of the equator | Acknowledgement that the focus will now turn to the nexus between carbon sequestration and food production | In the next 2 or 3 decades Flannery’s (2008) opinion is the point of no return will be exceeded |

| Live sustainably | Even climate skeptics now admit it’s real | The system is in a vicious circle of positive feedback | Point of no return is less than 20 – 40 years away | Suggests giving away intellectual property in clean coal tech’ to developing countries whose economies thrive on coal | Humankind has transformed these forests into farms, cities and useless grassland over 100 years | Focus on pyrolysis (i.e. heating biological matter in the absence of oxygen) to produce charcoal which can be reused to re-fertilize soil | Drastic strategies are considered (i.e. pumping sulphur dioxide) into the atmosphere to cool climate |

| Strong Judeo-Christian influence but admission that his ideas are in opposition | Climate science has linked humanity to global warming | Scientists predictions using upper and lower level projections are at upper levels | IPPCC projections assume reductions will happen… hence why their projects are low | Clean coal and geothermal energy should become the backbone of Australia’s new energy economy | Forests capture and release carbon in effect they are the worlds lungs. Cutting or burning them down quickens the release of carbon | By product of oil or gas can be reused to power the farm. All of this slows the carbon cycle. | Causal teleological argument of making trade offs between worst case scenarios |

| A full look at living sustainably is beyond the scope of the paper | Systematic approach: Earths organs – crust, air, water | Polar ice caps melting, not reflecting suns energy therefore contributing to warming | Emissions are increasing and efficiency not occurring | Carbon trading scheme is required | Government involvement fails to establish the need for change at the grass roots level | Hasn’t been adopted because of slow moving cultural acceptance, predominance of family businesses (i.e. that’s the way dad and grandpa did it) and its expense. | Sacrifice now so that future will benefit – extend the 8th commandment to future generations |

| What is our purpose as a species? | Crust provides coal, oil, natural gas and limestone, when burnt releases carbon | Models have not been able to replicate the changes…flying blind | Global energy sources need to change | Government and industry are required to take the long view | Suggests a new economic carbon sequestration model which puts socially and environmentally conscious capital holders with poor farmers to buy climate security | Holistic farm management versus common farming practices | Social Darwinism is not sustainable i.e. everyone will lose |

| How does the earth work? | Water covering 71% of planet draws carbon from atmosphere very slow process | WWF no longer trying to protect the arctic… its too late | Humankind has faced adversity before (i.e. WW2) and developed astonishing technological breakthroughs | Offers solutions and a perceived future around carbon neutral cities built around geothermal power sources | This process will educate the farmers in sustainable practices as well as bring them up to a better life (i.e. by distributing wealth for global carbon security) | Holistic farm management has an capped limitation (i.e. not scalable and not subject to Taylors (1911) theories of scientific management) | Pulling minerals out of the earth is like a genie in a bottle that cannot be returned |

| Personal search for meaning | To much carbon produces carbonic acid damaging life including carbon sequesters including algae | Other pollutants are masking the effects of warming (i.e. sulphur dioxide) | Developing countries will not change their coal use | Australia is lacking at adding value to its mineral resources | Topic of meat eating is raised and difference between high intensity production versus holistic farming drawn | Australia has become expert at mine-site remediation. Now attention must focus further afield | |

| Earth was not made for us, we were made for Earth | Atmosphere is the smallest organ (aerial ocean) | ¾’s of the warming effect will be felt in the next 250 years | Leadership and vision at an industrial and government level is lacking and the system of ownership and responsibility is complex… Australia’s attempt at leadership is too little | Examples of vision and change in Iceland, UAE and Denmark | Sustainabilitarian diet (i.e. eat what is in season or available within a close geographic area) | Humanity is part of Gaia not apart. Once recognized it will drive political, economic and social agendas | |

| Humanity is part of the Gaian system, not apart | We notice pollution in the air but don’t in the sea because of relative size | The tipping point has past but humanity has not yet reached the point of no return… we still have time | Clean coal technology provides some short term answers | New energy sources provide opportunities never envisaged (i.e. Danish excess wind power for electric cars) | Labeling system to advertise the carbon miles to develop a choice system that allows society to make value choice | Great change is required as humanity has never lived sustainability | |

| Zero impact is delusional | Shuffling of matter between the three organs is at the heart of the problem | Make full use of the existing tools and invent new ones to de-pollute and avoid Lovelock’s (2006) scenario | The problem needs to be viewed in stages with government leadership required | Humankind has socially evolved eradicating social injustices and technological advancements (i.e. faith in human kinds ability) | |||

| History of life = increasing complexity and efficiency | Carbon imbalance of our own making | Failure results in irrelevance of all of humankinds achievements | |||||

| Humanity is poised to become Gaia’s brain to assist in regulation by becoming Gaia’s consciousness | |||||||

| Search for sustainability is an uncertain experiment |

Source: Adapted from Flannery (2008)

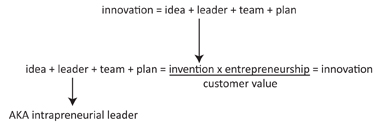

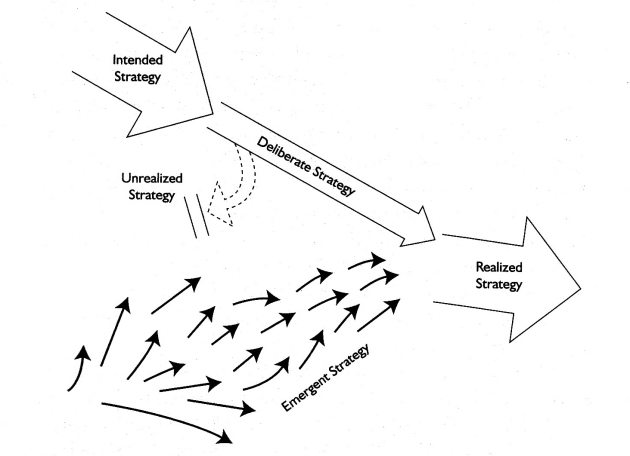

Integral Analysis

An analysis of the text will be attempted in the style of Rowe (2005) to visualise which areas of Wilber’s (2001) quadrant have been addressed. It’s posited that this will assist the analytical process providing “structure and rigour” (Rowe 2005). Each section is colour coded providing clarity at an individual systematic including holistic level (Meadows 2008 ; Nisbett et al. 2001). It should be noted the results are based on subjective interpretation not objective/quantitative methodologies.

Figure 1: Four Quadrants Now or Never Graphical Representation

Source: Adapted from Wilber (2001) and Rowe (2005)

Flannery (2008) posits humanity’s role is to act as the Gaian brain. This predicates an evolutionary process of thinking at higher orders than purely cognitive neocortex thought (MedicineNet 2003). By stating humanity’s position in this way the ontological and philosophical question of being and meaning is posed in practical language (UL). What is humanity’s purpose (UL, UR)? What structures need to be built to fulfil that purpose (LR)? What barriers to change exist (UR, LR, LL)? How can humanity agree and share the planet and its resources (LL, LR)? What is my and our purpose in the grand scheme of life on earth (UL, UR, LL, LR)? Although it might be found that the devil lies in the detail and not every chapter reaches higher orders within the quadrants, taking this approach wouldn’t do justice to Flannery’s (2008) overall intention. Subsequently, it stands to reason that the text would start and end at higher spiral, philosophical, ontological, phenomenological and temporal orders. This follows a logical and linear process of alerting the reader of his intentions, in the middle provide practical examples of alternate futures whilst re-enforcing his intentions and the requirement for change at the conclusion.

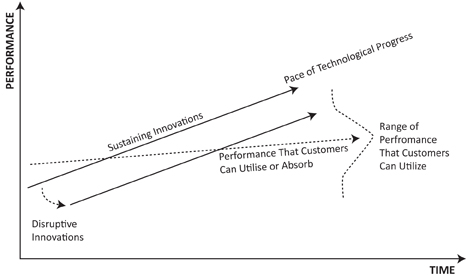

Spiral Dynamics (UL Quadrant)

In an attempt to illustrate the highest level of consciousness Flannery (2008) communicates, spiral dynamics (Beck & Cowan 1996) has been utilised (figure 2). Each chapter is colour-coded and plotted to represent its highest tier therefore highlighting inclusion of lower tiers (Beck & Cowan 1996). Justification and examples are provided in each transpersonal wave (Wilber 2001) in the following sections. Lower tiers not identified won’t be analysed due to theory of inclusion. Chapters are interpreted as parts rather than as a whole separating overall intent from merit of each argument.

Figure 2: Now or Never Tiers of Spiral Dynamics Consciousness

Source: Adapted from Wilber (2001) and Beck and Cowan (1996)

Blue/Orange

The rationale for including ‘Trees for Security’ at this lowest overall tier, is Flannery’s (2008) use of a system of economy, strategy, and commerce creating a virtual marketplace where carbon security is traded. It’s also due to the acknowledgement of missing cogent argument particularly in the case of economics (elaborated in further sections). By creating this system Flannery unwittingly advocates a society where rules and boundaries appear for future reward so that poorer communities become self-sufficient and materialistic (Beck & Cowan 1996 ; Hayward 2011).

Orange

‘Revolution in the Feedlot’ is an example of providing the reader with alternatives proving other possibilities than accepted paradigms. The intention is to manipulate via stating a main point, and providing validation/evidence in four areas; pyrolysis, holistic farming, sustainabilitarian diet and carbon labelling. This is pure strategic argument illustrating that technology and wisdom can solve the problem (Beck & Cowan 1996 ; Hayward 2011). Flannery (2008) fails to explain how predominant management/efficient manufacture theories such as Taylorism (1911) might (not) work. This missed opportunity allows his economics exploration to be questioned.

Orange/Green

‘The Coal Conundrum’ and ‘Geothermia’ state the use of coal, particularly in China, whilst acknowledging opposition to helping the opposition through carbon transfers is an unavoidable reality. However this is where Flannery’s (2008) economic argument becomes paradoxical. He advocates giving away clean coal technology (which has a cost and ongoing economic value) whilst also promoting Australia’s leadership position to develop new technology in order to economically benefit. Concurrently, advocating the building of cities based around 75-year output energy sources is also economically questionable. Although his intentions are noble highlighting an Islamic ‘Blue’ undemocratic non-pluralist country such as UAE also draws criticism[1].

Green

A ‘New Dark Age’ is manipulative in trying to illustrate Lovelock’s (2006) and Flannery’s (2008) different futures. It’s intention is to cause the reader to question the rationality of the climate data, provide an abhorrent future context so that sacrifices are made now for the greater good (Beck & Cowan 1996 ; Hayward 2011). By alerting the reader there’s still time before reaching the point of no return the reader is able to consider their actions and future in the wider context.

Yellow

Although largely problem and ‘matter of fact’ oriented ‘The Climate Problem’ follows the logic of humanities integral part of the world and its system (Beck & Cowan 1996 ; Hayward 2011 ; Wilber 2001).

Yellow/Turquoise

It’s fitting the first and last chapter of Flannery’s (2008) book reach the highest spiral discovered in analysis. This indicates that alerting the reader to his own personal journey of discovery, whilst linking it to humanity’s purpose in the Gaian system acting as the brain and admitting that it’s an uncertain future/experiment provides space for debate/dialogue. This touches the boundaries of holism through searching and communicating guiding principles within life and self (Beck & Cowan 1996 ; Hayward 2011 ; Wilber 2001). For this reason the text as a whole can be considered at this and inclusive of lower hierarchies (Beck & Cowan 1996).

Thought Methodologies

At surface value one might be tempted to pigeonhole Flannery’s (2008) thesis as only Platonic thought (Bok 2011) in that a logical either/or argument has been developed that any rationale minded individual can assimilate. This could be indicative of the difference between a warning system and solutions, however one must question whether this is the sole purpose or are there deeper levels of thought at play? It should be noted that throughout the text, systemic thought (Meadows 2008) is utilised to define humanity’s purpose in a system at physical and metaphysical contexts and how change influences humanity’s relationship within the system. This process enables the possibility of dialectic thought (Bok 2011) to occur of and/also. For this reason it’s possible to assert that oceanic thought of “not-only-but-also” (Bok 2011) has been utilised through a circular process of beginning with one concept (i.e. humanity’s purpose in a wider system), exploring possibilities to build the discussion and then finally returning to the original concept. By focusing at a logical either/or level dismisses the possibilities to engage in a wider discussion that is presently needed and is why the likes of Abbott (2011) have derailed the very dialogue and requirement for change Flannery (2008) elicits.

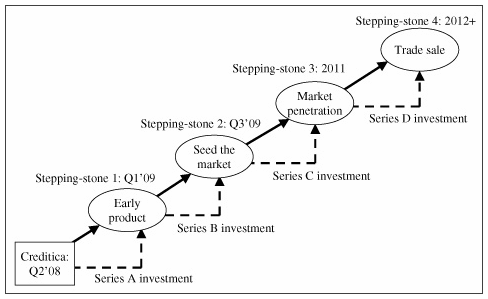

Change

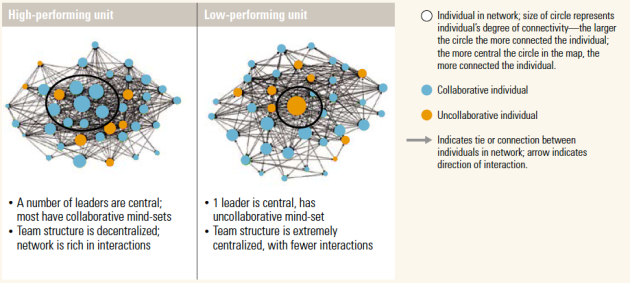

Wilber (2001, p 6-13) illustrates that just under 90% of the global population[2] hasn’t exceeded the orange tier of consciousness yet they hold 86% of the power. This is further validated by cognitive psychologists, Kegan and Lashkow Lahey’s (2009) finding that < 1% achieves the tier of self-transforming mind (figure 3 and appendix A). Their work follows Heifetz’s (2009) theories of adaptive change, acknowledging that response utilising cognitive mental maps and technical know-how rarely solves unique sociological adaptive challenges (Kegan & Laskow Lahey 2009).

Figure 3: Tiers of Adult Mental Complexity

Source: Kegan & Laskow Lahey (2009, L 641)

Flannery’s (2008) contribution to society’s need to rise above cognitive ‘what am I /we aware of’ (Bok 2011) consciousness asks the reader to challenge their values, assumptions, beliefs and expectations (Clawson 2006) on humanity’s place on Earth, including questioning Abrahamic theological constructs of Earth is ours rather we are Earth’s (Flannery 2008). By challenging the reader, Flannery (2008) enables the possibility of the aforementioned 90% of the world or the socialised or self authoring minded people to question their ALPHA realities moving them to GAMMA states with the possibility for DELTA transformation (Beck & Cowan 1996) (figure 4).

Figure 4: The Sequences of Values Change in Spiral Dynamics

Source: Hayward (2011)

Practicality – Other Futures Theoretical Models

Flannery’s (2008) thesis could be categorized as emancipatory (Slaughter 1999 ; Voros 2011a) due to its intention to educate and catalyse action at a societal level. For this reason it would seem safe to assume that the depth of thinking is problem-oriented. However this interpretation is incorrect due to Flannery’s (2008) conception of ontological being, philosophical meaning and purpose to influence worldviews through epistemological means (Slaughter 1999 ; Voros 2011a). Subsequently, it’s logical to posit that the breadth is equivalent to spurring a civilisational futures movement (Slaughter 2005) through requirement for action. Henceforth it’s suggested the thesis is somewhat critical through analysing the problems to pose different futures but also could be anticipatory action (Inayatullah 2005 ; Voros 2011a) learning due to Flannery’s (2008, p 8 ) citation that humanity’s “search for sustainability is thus an uncertain experiment, which must inevitably see setbacks and failures.”

Flannery’s (2008) intention is to highlight the weight of the past through exploring the barriers to change by illustrating the push of the present (i.e. phenomena and situations that have defied accepted paradigms) by constantly pulling positive and negative images of the future (Inayatullah 2003). This helps the reader interpret difficult territory whilst being able to keep an open mind.

What’s missing?

It must be admitted that this is where the ‘detail devil’ raises its head but there’s a need to highlight the issues so fruitful discourse can continue rather than final judgement occur. Flannery’s (2008) hypothetical Geothermia has previously been questioned however analysis brought forward to present day indicates, Geodynamics is still nine years away from commercial operation with a share price that has lost 90% of its value (Geodynamics 2011a, 2011b). The reality is that Flannery (2008) use of economics isn’t cogent, not questioning the system of economics to which humanity is beholden. This lack or exploration leads him to contradict himself continuously whilst being ignorant of the prominent model of production in Taylorism (1911) to quickly generate economies of scale and swifter return on investment. He discusses the need to give away intellectual property, which has an economic value but further on discusses situations where being an innovative leader brings, economic benefit. Precedence would dictate that all intellectual property should be given away and possibly owned by the state/planet in a Marxist future (Marx 1995)?

Figure 5: Cooper Basin Development Plan, Flannery’s ‘Geothermia’

Source: (Geodynamics 2011b)

Figure 6: Geodynamics Share Price

Source: (Geodynamics 2011a)

Furthermore it’s interesting that Flannery chooses to capitalise the word Earth in an attempt to deify the planet. This is inline with many religious concepts but in opposition to the three Abrahamic religions (i.e. Judaism, Christianity and Islam). If he were to be more explicit on these fronts, individuals who might be at lower orders of consciousness might not react in an adversarial way.

It seems the issues that Flannery (2008) outlines can be fixed by either cultural/social or technological change. He opts for technological change due to an overt optimism that humankind has the collective knowhow to extricate itself from dire situations. An example of such, and in opposition to Lovelock’s (2006) premise that humanity is destined for doom, Flannery (2008) posits, “this is not to say that humanity will fail. Indeed, at moments of crisis, such as during the Second World War, astonishing breakthroughs in technology and manufacturing occurred. The problem is that, so far, humanity has failed to see the need for urgency” (Flannery 2008, p 27). This proclamation defines that his communication of the needed process for change through uncertain experiment (Flannery 2008) requires continued focus on the internal nature of humanity to convince the masses who would only see this discourse at a problem solution level.

Conclusion

Flannery’s (2008) thesis now dissected utilising futures tools may seem like it’s flawed. However a different view is advocated. This different view should consider that Flannery’s (2008) aim is to educate and create necessary debate in order for the collective of humankinds ability to generate solutions. One couldn’t fault him on a failure of nerve or imagination (Clarke 1999 cited by Voros 2011b)

It’s been found that Flannery has taken a teleological rather than a deontological approach to try and cater for a wider audience without ‘scaring them off.’ Subsequently, it’s ironic that judgement must be made as to the suitability of Flannery’s (2008) text. This indicates a preference for Platonic thinking when in the view of the author who has analysed and reviewed Flannery’s (2008) work, why can’t it just be (Bok 2011)? If that were the case, platforms and gaps in the work could be identified in order that productive process of thought (Bok 2011) (i.e. other than right or wrong) and building on the discourse can occur. If this were the case and intended aim then the current amplified issues to which Flannery (2008) attests might be minimised.

List of References

Beck, DE & Cowan, CC 1996, Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership and Change [Kindle Edition], Blackwell Publishing, Malden, Massachusetts, Amazon Digital Services.

Bok, B 2011, Lecture 5: ‘Know Thyself’: Systems thinking, HBF540 Knowledge Base of Future Studies, Swinburne University of Technology, 29 March 2011.

CIA 2011, World Factbook: United Arab Emirates, viewed 4 April 2011, <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ae.html>.

Clawson, JG 2006, Level Three Leadership: getting below the surface, 4th edn., Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Flannery, T 2008, Now or Never: A Sustainable Future for Australia?, Quarterly Essay 31. Black Inc (online).

Fordham, B & Abbott, T 2011, Tony Abbott interview with Ben Fordham, Radio 2GB – Julia Gillard’s carbon tax, viewed 29 March 2011, <http://www.liberal.org.au/Latest-News/2011/02/25/Interview-with-Ben-Fordham.aspx>.

Geodynamics 2011a, Geodynamics Limited Share Price Information, viewed 4 April 2011, <http://www.geodynamics.com.au/IRM/content/shareholder_sharepriceinfo.html>.

Geodynamics 2011b, Progress to Date, viewed 4 April 2011, <http://www.geodynamics.com.au/IRM/content/about_progresstodate.html>.

Hayward, P 2011, Clare Graves – Levels of Existence Theory [Lectopia Recording], viewed 15 March 2011, <http://media.swinburne.edu.au/su94heeb/afi/hsf601/PHayward20050307-01_BBand_files/fdeflt.htm>.

Heifetz, R, Grashow, A & Linksy, M 2009, The Practice of Adaptive Leadership [Kindle Edition], Harvard Business Press, Boston, Massachusetts, Amazon Digital Services.

Inayatullah, S 2003, ‘Teaching Future Studies’, Journal Of Future Studies, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 35-40,

Inayatullah, S 2004, Five Futures for Muslims, viewed 5 April 2011, <http://www.metafuture.org/Articles/Five%20Futures%20for%20Muslims.pdf>.

Inayatullah, S 2005, ‘Methods and Epistemologies in Futures Studies’, in RA Slaughter, S Inayatullah and J Ramos (eds), The knowledge base of future studies, 5 vols, CD-ROM, Professional edn, Foresight International.

Kegan, R & Laskow Lahey, L 2009, Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization (Leadership for the Common Good) [Kindle Edition], 1 edn., Harvard Business Press, Boston, Massachusetts, Amazon Digital Services.

Lovelock, J 2006, The Revenge of Gaia [Kindle Edition], Penguin Books, London, England, Amazon Digital Services.

Marx, K 1995, Capital, Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Meadows, DH 2008, Thinking in Systems: A Primer [Kindle Edition], Chelseas Green Publishing, Amazon Digital Services, Vermont.

MedicineNet 2003, Definition of Neocortex, viewed 10 April 2011, <http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=25283>.

Nisbett, RE, Choi, I, Peng, K & Norenzayan, A 2001, ‘Culture and Systems of Thought: Holistic Versus Analytic Cognition’, Pyschological Review, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 291-310,

Rowe, R 2005, ‘The Modern 20th Century Society and a New Idealogy: The Genesis of Future Studies’, in RA Slaughter, S Inayatullah and J Ramos (eds), The knowledge base of future studies, 5 vols, CD-ROM, Professional edn, Foresight International.

Slaughter, RA 1999, Futures for the Third Millennium in Towards a Wise Culture, CD-ROM, Professional edn, Foresight International.

Slaughter, RA 2005, ‘Futures Concepts’, in RA Slaughter, S Inayatullah and J Ramos (eds), The knowledge base of future studies, 5 vols, CD-ROM, Professional edn, Foresight International.

Taleb, NN 2008, The Black Swan [Kindle Edition], ePenguin, Amazon Digital Services.

Taylor, FW 1911, The Principles of Scientific Management [Kindle Edition], Public Domain Books, Amazon Digital Services.

Voros, J 2011a, Lecture 2: Some Models for Understanding the Futures Studies Territory, Presented by B Bok, HBF540 Knowledge Base of Future Studies, Swinburne University of Technology, 8 March 2011.

Voros, J 2011b, Lecture 3: Futures Concepts and Tools, HBF540 Knowledge Base of Future Studies, Swinburne University of Technology, 9 March 2011.

Wilber, K 2001, A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality, Gateway, Park West, Dublin.

Appendix A: Three plateaus in adult mental development

Figure A.7: Three Adult Plateaus of Thought

Source: Kegan & Laskow Lahey (2009, L 450)

[1] Flannery (2008) raises the UAE as a beacon of hope for carbon neutral metropolises but fails to divulge that the UAE’s economy relies on oil and gas and it’s not a democracy with its legal system a mix of Sharia and civil law (CIA 2011). When one compares an Arabic country with a majority population who look to the past for boundaries and rules (Inayatullah 2004) with a more heterogeneous society such as Australia it must be taken with caution.

[2] It should be noted that Wilber’s (2001) mathematical percentage calculations are incorrect but the point is useful.